Twisted tale into corruption [Excessive Legal billings and corrupt state officials]

The Attorney General is empowered to brief private lawyers/counsel to act for the State. This occurs when there is need for particular expertise or the Attorney General is unable to undertake the work itself. From Finance Department records a Commission of enquiry found that over the period 2000 to 2006 the State incurred liability in payouts of approximately K100 million in legal fees. The Inquiry saw that there has been no compliance with the Public Finances (Management) Act procedures of expenditure for approval prior to engaging in those brief outs. A Commission of enquiry after making extensive examination of these payments with ready assistance from all the law firms concerned except Paul Paraka Lawyers which has been the recipient of at least the K41 million in brief out fees for January 2003 to August 2006 noted in NEC records.

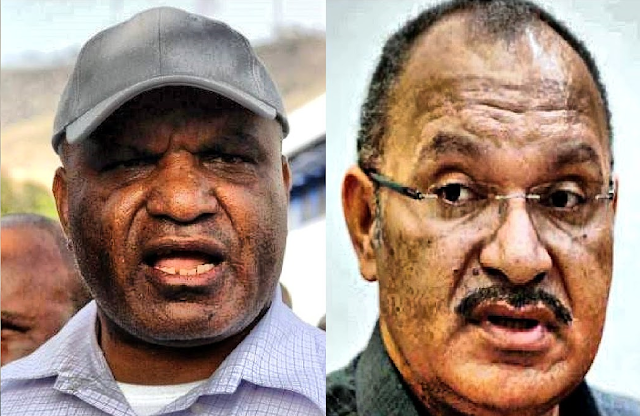

Let me illustrate what I mean by excessive legal fee with our so called Chief Secretary of the National Government, Mr. Isaac Lupari. Mr Isaac Lupari sued the State for breach of four separate contracts that were entered into as Secretary for the Departments of Finance, Defence, DPM and Transport in that order. He claimed that he had been unlawfully terminated from all those positions after serving short stints in each and claimed the balance of all pay and entitlements for the unexpired period of all four contracts while he was still engaged by the Government of PNG in various capacities and paid very well in various Advisory roles.

In 2002 Mr. Lupari reached an understanding with the newly installed Somare Government that he would be appointed as the new Ambassador representing Papua New Guinea at the European Union based in Brussels. In gratitude Mr. Isaac Lupari agreed to drop all four court actions he had filed.

Having secured the job of European Union Ambassador, Mr. Lupari reneged on the above deal in which he had promised not to pursue his claims against the State. A short five months after he had withdrawn the first lot of claims he instructed his lawyers (Paul Paraka Lawyers) to file the same court actions again. Less than two months after the second lot of Writs were filed, a Deed of Settlement was signed on the 03rd of March 2003 by Mr. Zachary Gelu acting on behalf of the State, which the state paid a substantial K 3, 703, 461. 21. Of the four matters, the taxation officer, taxed legal fees for Paul Paraka at K200, 000. 00 each totalling up to K800.000.00. After all this tax payers money was paid to a greedy individual and his lawyer, he was reappointed on the very same day to the position of Secretary for Defence.

Coming back to the Paraka Saga which began in 2002 when the late Francis Damem was the Attorney General under the Somare Government. On 19th December 2002, the then Attorney General, the late Francis Damem, began briefing-out to Paraka Lawyers starting with 56 matters (Paraka Lawyers were to provided Legal Services to the state). These were followed by two further briefs-outs of 10 and 100 matters respectively on 23rd March 2004 and 6th December 2004. That brought the total briefs to Paraka to 267 matters. However, for reasons only know to Paraka Lawyers and those involved in its facilitation, the State paid a total of K41, 999, 648.32 to Paraka since 18th September 2002 when a sum of K3, 993, 497.70 was paid. You can see that the payment was made about two months prior to the first brief out on record dated 19th December 2002.

On 6th June 2006, Mr. Joshua Kalinoe, then Chief Secretary to the National Government issued a letter directing Mr. Gabriel Yer, the then Secretary for Finance to cease all further payments to Paraka. Then by letter dated 11th October 2006, the then Minister for Justice Hon. Bire Kimisopa, with the endorsement of the National Executive Council (NEC) by decision dated 1st November 2006, decided to establish a Departmental Inquiry in the legal brief-outs and payment of the substantial sums of money to Paraka Lawyers. Meanwhile, the decision also amongst others terminated all brief-outs and withdrew all files and stopped all payments to Paraka. On 16th October 2006, the then Attorney General acted on the Minister's decision. Paraka responded with the issuance of two separate judicial review proceedings, respectively referenced, OS No. 829 of 2006, on 10th November 2006 and OS 876 of 2006, on 29th November 2006.

Independence of Judiciary in Question.

On 17th November 2006, which was seven days after the issuance of the first of the two proceedings, the late Hinchliffe, J issued that the stop-payment directive of the Chief Secretary through his letter dated 6th June 2006, to the Acting Secretary for Finance is stayed pending the determination of the substantive judicial review and the state identify funds and issue a special warrant for the sum of K6, 499,436.44 to the Second Respondent forthwith, who in turn shall arrange the payments to be made to the Plaintiff by or before 1:30pm the same day which was Friday 17th November, 2006 which can be seen as a very desperate move.

The following day on 03rd March 2007, the State lodged an appeal against the orders of Hincliffe JJ. Pending a hearing and determination of the substantive appeal, the State, on 5th March 2007, successfully sought and obtained a stay of Hinchliffe J.'s orders of 02nd March 2007.

The Supreme Court later held that although leave for judicial review was separately sought and granted, the motion was filed and service prior to the grant of leave for judicial review. Paraka could not legally do that, until after the grant of leave for judicial review, they also questioned the fact that Hinchliffe, J could make order regarding the substantive Issue in a Judicial Review and the fact that he could order the state to make payment to Paraka Lawyers within the same day on two different Judicial Review and restraining all parties or their agents to restrain or cause to frustrate the process of Payment. As mentioned the Proceedings of the substantive issue was still pending.

In a Supreme Court case in 2014 presided by Kandakasi, David, Murray, JJ. found that Paraka did not demonstrate to the Courts satisfaction that he properly secured the brief-out or engagements from the State for the provision of legal services. This proceeded on the basis, that no evidence was produced before the trial judge and drawn to their attention in the appeal that the due process under the Public Finance (Management) Act was followed. Similarly Paraka failed to demonstrate to their satisfaction that, he entered into a legally binding agreement with the State on the terms of his engagement. Further, he failed to demonstrate to their satisfaction that, he rendered his bill of costs in taxable form as required and in accordance with the Lawyers Act, which was accepted by the State or failing such acceptance, taxed with a certificate of taxation issue, which then formed the foundation for his claims and the orders the learned trial judge eventually issued. Furthermore, the exact amounts in excess of K6 million each were not specifically pleaded. That legally served as a bar to making any orders for any sum of money. Despite that, the learned trial judge erroneously made orders for the payment of such large sums of money.

the presiding judges found that the decisions and orders of the learned trial judge (Hinchliffe, J) were highly irregular and seriously flawed from the outset. They found that, if the learned trial judge correctly directed his mind to the matters he would not have arrived at any of the orders he arrived at safe only for the grant of leave for judicial review. Hence, there was a serious impediment to the learned trial judge making the orders he made. The orders also had the effect of improperly, interfering with the due process of financial administration of the State through the Departments of Finance and Treasury as well as that of the Bank Papua New Guinea

From a reasonable person’s point of view it can be clearly concluded that the presiding judge was compromised, this then begs the question; to what extent is our judiciary transparent?

Look at the allegations against the Supreme Court judge, Bernard Sakora who accepted a K100, 000 payment in 2009 from a company linked to Paul Paraka Lawyers. Justice Bernard was arrested after ongoing investigations to the payment of the legal bills to Paraka Lawyers where this payment to the judge was discovered and the investigation conducted into the payment made. Justice Bernard Sakora has presided over several cases related to the payment of those bills and involving Paul Paraka Lawyers.

Sakora issued an injunction (stop or preventive order) in 2010 in favour of Paul Paraka and former solicitor-general Zacchary Gelu banning the implementation and publication of the report of a Commission of Inquiry into fraudulent legal bills charged to the Government.

In February 2016, he issued a stay order preventing anti-corruption officers from executing an arrest warrant for Prime Minister Peter O'Neill, who is accused of authorising payment to Paul Paraka Lawyers.

Mere beginning of a Legal battle

In 2010 the Supreme Court presided by Salika DCJ, Lenalia & Cannings JJ refused the application filed by Paraka Lawyers to stay the decision of the National court presided by Hinchliffe, J to release the fund to Paraka Lawyers.

Despite the Supreme Court orders and refusal of appeals by Paraka Lawyers, the State under the O’Neill government and his tea boys, the so called Finance Minister, Mr. James Marape decided to Pay Paraka Lawyer K71 Million out of the blue as an off court settlement in spite of the controversial issues regarding hefty legal bill concerning the same law firm were still pending. Note that the substantial K71 million was paid between 2012 and 2013.

When independent and transparent bodies were asking questions into the legal billings, O’Neill decided to issue a Directive on 13th May 2013 instructing amongst other things that "...a High Level Investigation must be conducted into the legality of the payments and settlements. The investigation team should be made up of Taskforce Sweep and Police Fraud Squad, with the support of the Australian Federal Police and Interpol."

By a letter dated 15th January 2014, the then Commissioner of Police Toami Kulunga invited Mr Marape for an interview in relation to the alleged fraudulent payment of legal bills to Paul Paraka Lawyers explaining that "Police through the work of the Task Force Sweep have analysed the information that was gathered and are of the opinion that there is evidence of criminality implicating yourself in the complaint, hence the need to speak to you."

Through his lawyer, Mr Marape requested for the interview to be deferred until the determination of certain National Court proceedings that had emanated from steps taken by four policemen (not part of the Taskforce Team) allegedly at the behest of Hon.

In one of those proceedings (OS No. 10 of 2014) consent orders were entered into, the effect of which included the Police being restrained from arresting Mr O'Neill and Mr Marape pending determination of that proceeding. On 14th March 2014 Mr Marape filed this proceeding for himself and the State seeking amongst others, an order for the taxation of a total of 2,716 legal bills of costs charged by Paul Paraka Lawyers and claimed for legal work rendered to the State between 6th May 2003 and 30th October 2006.

Transparency and competency of the NEC’s decision making power

Despite O’Neill’s statement made on the 13th of May 2013 to allow the taskforce sweep team to investigate the matter, the taskforce sweep was disbanded in 2014 as a result of the Taskforce sweep’s finding and report to the then police commissioner Mr. Kulunga, as mentioned Mr. Koim submitted a report on 5th May 2014 to the then Commissioner of Police Sir. Tom Kulunga that there was sufficient evidence to prosecute the Prime Minister for alleged involvement in the fraudulent payment of money to Paul Paraka Lawyers.

The allegation was that the Prime Minister had signed a letter addressed to the Minister for Finance and Treasury, Hon, Don Polye dated 24th January 2012 directing payment for outstanding legal costs to Paul Paraka Lawyers.

On 15th May 2014 Commissioner Kulunga was convicted for contempt of Court by the National Court constituted by the Deputy Chief Justice for breaching an order of the National Court to reinstate Mr. Geoffrey Vaki to his former position as Assistant Commissioner of Police.

On 30th May 2014 the Constitutional Amendment (No. 40) (Independent Commission Against Corruption) Law 2014 was certified.

On 12th June 2014 on the direction of Commissioner Kulunga warrant of arrest was obtained for the arrest of the Prime Minister for official corruption under section 87 (2) of the Criminal Code.

On 16th June 2014 Commissioner Kulunga sent a letter to the Prime Minister inviting him to attend an interview with the Police National Fraud and Anti-Corruption Directorate at Konedobu which the he Prime Minister did not attend.

On the same date (16th June 2014) the NEC approved to advice the Head of State to revoke the appointment of Commissioner Kulunga as Commissioner of Police and appoint Mr. Vaki as Acting Commissioner of Police. It was, accordingly done.

On 18th June 2014 the NEC, having regard to a policy submission, noted the progress made to establish Independent Commission Against Corruption and approved that the TFS be abolished. It was, accordingly done.

On 24th June 2014 the NEC, again having regard to a policy submission, approved the establishment of an Interim Office of Anti-Corruption and appointed Mr. Ellis as Chairman (who was an expatriate and a retired judge). It was also done. It also directed that all files belonging to the TFS were to be transferred to the Interim Office for Anti-Corruption.

I can only conclude that decisions of the NEC could not have been coincidental at the time when the Prime Minister was being investigated, and moves were made to have him arrested and charged for official corruption for his alleged involvement in the alleged fraudulent payment of monies to Paul Paraka Lawyers. It can be concluded that it was a deliberate act and ploy to frustrate and stop the TFS from proceeding with the arrest and charge of the Prime Minister. The NEC’s biasness of the decisions cannot be underestimated nor ignored so as it is apparent that the NEC was driven by bad motive to arrive at the decisions it did.

Legally diverting the course of justice

When the Public Prosecutor Pondros Kaluwin tried to refer the O’Neill to a leadership tribunal, O’Neill as a desperate move filed proceedings at the National court to stop Kaluwin. On 20 November 2014. O’Neill commenced proceedings by originating summons, seeking declarations and injunctions regarding the decision of the Public Prosecutor to refer him to a leadership tribunal on a matter of alleged misconduct in office. O’Neill sought, in relation to the Public Prosecutor: declarations that the Public Prosecutor is not entitled to refer that matter to the tribunal and is not entitled to bring such proceedings against him, and a permanent injunction restraining the Public Prosecutor from referring that matter to a tribunal and from continuing proceedings concerning that matter.

It can be seen that the amended notice of motion was an abuse of process, as the question of whether any constitutional questions should be referred to the Supreme Court was properly a matter for the tribunal, which is the proper forum in which the question of referral to the Supreme Court of any constitutional questions should be raised, and the application for referral of constitutional questions, injunctions and a stay of the tribunal's proceedings was simply an attempt to prevent the tribunal from convening on 26 January 2015.

Mr. O’Neill filed a number of proceedings at the national court and the Supreme Court to stop the office of the public prosecutor and the ombudsman commission to set up commissions of enquiry and leadership tribunals.

Majority loosing a battle against an individual tyrant

When O’Neill was suspected of official corruption, an offence contrary to Section 87 of the Criminal Code. A warrant of arrest was obtained at the District Court on 12th June 2014 issued by the Chief Magistrate on the application of Chief Inspector Timothy Gitua of National Fraud Squad. The facts are simple and clear, The warrant of arrest was directed to amongst others, Chief Inspector Gitua to arrest the Prime Minister “as being an (sic) holder of a Public Office, charged with the performance of his duty (sic) virtue of his office, did corruptly direct to obtain a monetary benefit for Paul Paraka Lawyers in the discharge of the duties of his office as the Prime Minister.”

Before the warrant of arrest was executed or served, an application was made by the then Police Commissioner Geoffrey Vaki to have it set aside. Geoffrey Vaki wanted to have the allegation against the Prime Minister reviewed and assessed by an independent team of detectives, which can be seen as a load of cap, I’m not surprised he was dismissed in the police force almost three times.

O’Neill consented to the application but pointed out that the application for warrant of arrest was not supported by Information, a requirement which it asserted is mandatory under Section 8 of the Arrest Act.

On 4th July 2014 the the Chief magistrate dismissed the application, holding that a failure to produce an Information was not fatal to the issuance of the warrant of arrest. It was the warrant of arrest that is mandatory for the purpose of facilitating a lawful arrest of a person suspected of official corruption and which formed part of the process of police investigation.

Following its dismissal, on 14th July 2014 the First Plaintiff commenced this proceeding to review the decision of the First Defendant to issue the warrant of arrest at the National Court.

A recent Decision on Judicial Review presided by Justice Collin Makail was on two grounds;

The main ground was that the Chief magistrate acted without or in excess of her jurisdiction in issuing the warrant of arrest in absence of an Information contrary to Section 8 of the Arrest Act.

A further ground was that the First Defendant as a matter of law in issuing the warrant in circumstances in which there was no compliance with Section 8 of the Arrest Act. Amongst other things, the warrant of arrest did not disclose an offence known to law, and departs from the elements of an offence of official corruption required under Section 87 of the Criminal Code.

The two grounds were dismissed just this month August 8 2017 on the legal reasoning basis that the proceeding was an abuse of process and must be dismissed. Hence making the warrant of arrest effective again, however the A supreme Court issued an interim stay order on the arrest of O’Neill after leave was granted to appeal the National Courts decisions made this month. The decision of the National Court has been appealed and to be reviewed at the Supreme Court.

Why wasn’t O’Neill arrested, and can the police commissioner be charged for contempt for not arresting the O’Neill.

Arrest warrants are usually issued on the application of a police officer, usually a detective police informant. The process is commenced by Information, which would be a draft of a charge that would be subsequently laid and supported by evidence on oath by a police informant. The evidence would be in the form of affidavits or statutory declarations. Where documentary evidence is involved copies of the documents would be annexed. The content and context of the evidence must be such that they support the application for the issuance of an arrest warrant.

The District Court deals with applications for arrest warrants summarily and promptly. An application for an arrest warrant upon being registered at a District Court registry would commence the process. The material filed must disclose a probable cause for the issuance of an arrest warrant. Once registered the application would be brought promptly to the earliest available Magistrate.

The Magistrate would pursue the documentation and upon being satisfied that a probable cause is disclosed, the Magistrate would issue an arrest warrant. Usually, draft arrest warrants would be attached to the application which the Magistrate would sign off, seal it and hand it over to the police informant. In most cases, applications for arrest warrants are made in a Magistrates’ chambers. If a Magistrate is not available, applications for arrest warrants would be left at the registry.

A Magistrate would deal with it when possible. In that case, the informant would collect the sealed warrant later. It is as simple and straight forward as that. Delays in the process, if any, would be caused by the unavailability of a magistrate to deal with the application. Once an arrest warrant is issued, the police will be on their way to execute the warrant. That would happen even as the application papers and sealed registry copies of the arrest warrant are pending entry and archiving at the Court registry. Clearly therefore, the entire process, from filing and registration of an application to the issuance of an arrest warrant, may take as little as an hour or even less.

There are no calling and cross examination of witnesses or a trial or hearing in the normal sense. Even the person who is the subject of a warrant, who stands to be affected, is neither required nor given an opportunity to be heard or call his witnesses before a decision to issue or not to issue a warrant is arrived at. Clearly, therefore an application for an arrest warrant is purely administrative to assist police in their work and is dealt with summarily or administratively. This is necessary to ensure an offender does not escape arrest. Arrest warrants are applied for and obtained by the police to bring suspected offenders to the police station for interviews and eventual arrest if there is enough evidence to proceed with a criminal charge against the person arrested pursuant to an arrest warrant. Given that, no provision is made in the District Court Act or elsewhere authorizing a District Court Magistrate to make an order directing or compelling police to arrest a suspect.

Through the arrest warrant process, all that the police are doing is asking or seeking the permission of a District Court Magistrate to arrest someone. In so doing, they are effectively asking the Court to sanction an otherwise an unlawful act, the deprivation of a person’s liberty and to compel that person, who is usually a suspect to cooperate in ongoing police investigations, after which they may choose to formally charge and prosecute an offender or not. Seeking permission to arrest a suspect is what the process is all about and it starts and ends with the police.

There is usually no compulsion to have the arrest warrant executed. If on further consideration of the material the police acted on or on further investigations there is no disclosure of a criminal offence being committed or the evidence is not strong enough to secure a conviction, the police would be within their powers not to execute an arrest warrant and decide against going any further. In such a case, the probable cause ceases to exist and the need to execute the warrant becomes futile. Thus, the police have the discretion or the prerogative to decide whether or not to execute an arrest warrant and if it is to be executed, when. If a warrant is not executed, the police are not required to justify their choice not to execute the warrant or indeed for not arresting the suspect and bring him to the Court. Given that, there is no provision in the District Courts Act or any legislation for follow up or enforcement of arrest warrants. The police are of course accountable to their immediate superiors and ultimately the Commissioner of Police, for the choices they make on the execution of any arrest warrant.

Arrest warrants have to be contrasted with court orders issued in regular court proceedings which require obedience. Complying with court orders is mandatory for persons who are ordered or directed or commanded to do or take certain steps. Failing compliance of such orders will attract adverse consequences, including contempt of court proceedings. As may be apparent from what has already been said, there is a fundamental difference between arrest warrants and regular court orders.

The difference is in the fact that, in regular court proceedings, there must be a hearing where the party seeking the order and the party that will be affected by the order are fully heard or opportunity given for that before an order can be made. In some instance, as in urgent ex parte interim proceedings, where the rules of the Court or a positive law permits, court proceedings may be commenced and pursued to the exclusion of the other side. In those kinds of cases however, the court is required to be satisfied that a cause of action known to law is disclosed in the proceedings and the applicant is entitled to the relief or relieves the applicant may be seeking. In other words, the court must be satisfied that the applicant has made out his or her case both on the relevant and applicable law and the facts as opposed to a magistrate needing only to be satisfied that there is probable cause for the issuance of an arrest warrant.

You can see that the process is very simple, If he is innocent as he claims, then why is he prolonging the investigation wasting our tax payers’ money on hiring big gun expensive Queens counsels to fight a lengthy legal battle where we can solve it through a five minute police interview, I don’t see the logic.

Conclusion

In conclusion it can be seen that the O’Neill and his tea boys will fight this legal battle into the grave, it’s been years since investigation and allegations have been levelled against him and nothing has been done, it seems like the Executive, Judiciary and Legislator has taken sides to fight against the 8 mission people of the Nation. It’s time we do something in light of the current economic crisis and proliferating law and order problems or otherwise O’Neill will take us all into the grave with him.

Comments

Post a Comment

Please free to leave comments.